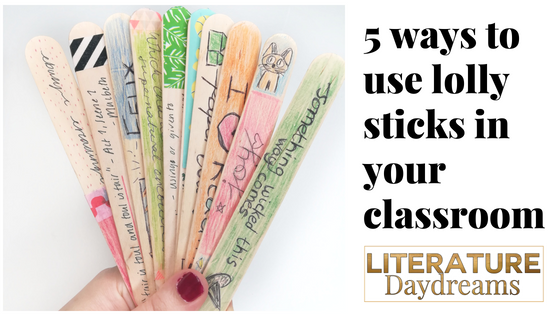

- in Classroom , Teaching tip

5 ways to use lolly sticks in your secondary classroom

If you’re anything like me, you have drawers or even cupboards of things you have bought for your classroom – just in case. I have about one hundred thousand lolly sticks*. Over the last year, I worked hard to use all-the-things. In the post, I am going to share 5 ways you can use all those lolly sticks in your secondary classroom!

1. Still great for names

Lolly sticks originally made their way into our classroom as a form of assessment. We wrote our students names on them. Then used them as a simple, low-tech random name generator. Well, they are still great for that purpose. You don’t necessarily need to use them as part of your questioning strategy every lesson. But mix things up using them every now and again.

Here’s what I do:

Hand out the lolly sticks to students at the beginning of the year. Set them a homework to decorate their lolly stick with their name and at least 2 images that show me something about their personality.

I stick them in a cup at the front my room and use them to:

- select students at random to answer a question or perform a task

- randomly assign pairs or small groups

- choose students at random for a positive call, email, or post-card home

- monitor missed homework (they get a red dot sticker on their stick)

So don’t discount using your lolly sticks for names still!

2. Bookmarks

Another way I use lolly sticks is as bookmarks for our class novels. We generally don’t have enough copies of our class novels to allow students to sign them out and take them home. In fact, often our teachers are sharing class sets of novels between and we have to juggle who is using the books during hour 1, hour 2 etc. I also don’t see my classes every day. In fact, some of my classes are one hour a week classes and I don’t see them except for that one hour.

So, bookmarks are one of the things that make my reading teaching easier. I used to use post-it notes and to be honest that was fine. But my lolly stick bookmarks have a two-fold purpose: they make a great bookmark and they can be used as a reading ruler.

Here’s how it works:

- Hand out a lolly stick to each student in your class.

- Ask them to decorate it with either a short quote about reading (I’d rather be reading) or a book they would love to recommend.

- Then when we start reading I ask every student to use their bookmark as a reading ruler. I model it. We practise. Rewards are given out for those who are doing it right.

- At the end of the lesson, everyone puts the bookmark into the book (at the right place) and returns to book to my box.

- The next lesson I hand out the books out and students get to discover a new bookmark. Each lesson they get to see/use a new bookmark.

It’s an easy and effective way to keep everyone on track. No issues with different page numbers in different editions of the novel and an easy differentiation tool.

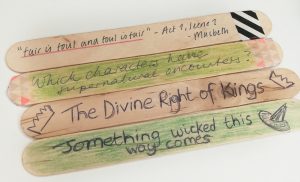

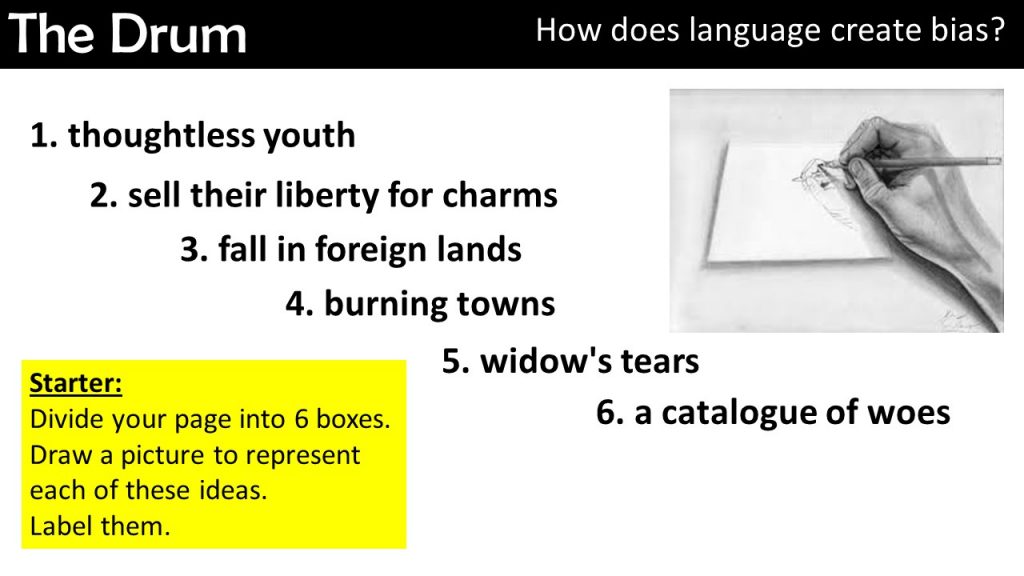

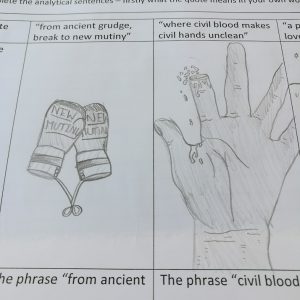

3. To help your study of literature texts

I also use them the most for extending and developing student responses to literature texts. Let’s take Macbeth for example. At some point early on in studying the text, I will hand out my unused lolly sticks to the students and ask them to write on them the names of characters, events, settings, themes, and relevant historical context facts. Once I have these I use them in a number of ways:

- Handout to students and ask them to link any class discussion to their own lolly stick.

- Ask them to form a question for the class based on their lolly stick.

- Challenge them to use their lolly stick information in any analytical writing we are doing.

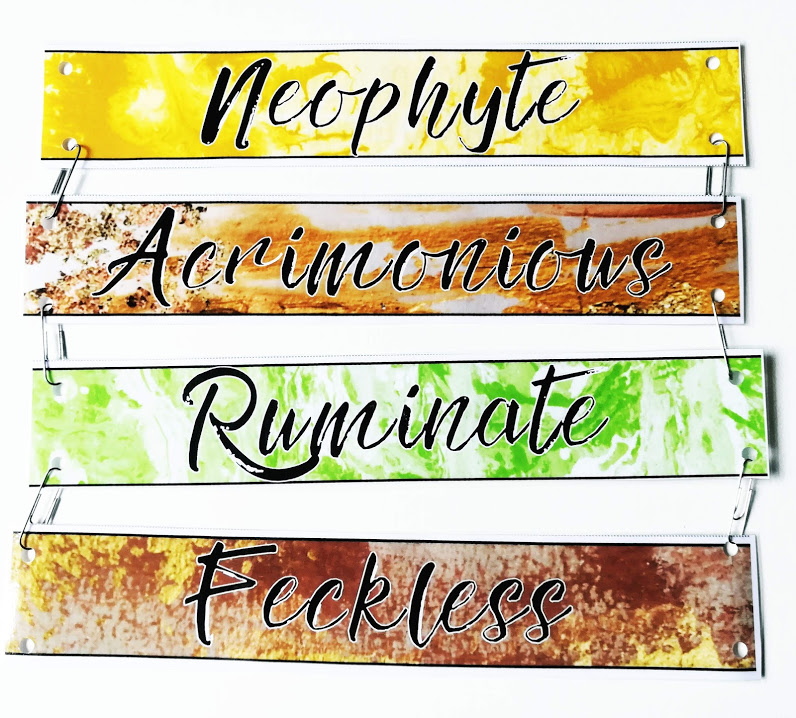

To take this further, I then start adding lolly sticks with key literary terms on (foreshadowing), with text-specific language (sycophant for example from Macbeth), or with essay writing challenge sentence starters (e.g. another way this could be interpreted is…).

By the end of studying a literature text, I normally have about 150+ lolly sticks to use for any number of quick quizzes, revision tasks, or extension ideas. Even better, when I move onto a new text but want to spiral back to review Macbeth (for example) then I can just grab a lolly stick and ask the class a question.

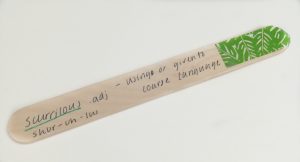

4. Awesome vocabulary

Idea 4 is one that I use throughout the year and I use across multiple classes. Simply, anytime we find a new vocabulary word that we love (last year one class was obsessed with the word incredulous), we write it onto 2 – 3 lolly sticks and put them in our vocabulary post.

5. Puzzle Paradise

The final idea for using up all those lolly sticks is to create puzzles for your students to solve. These are great ice-breakers, quick fixes for when you need 5 minutes, or discussion prompts.

Here’s what I do:

- Lay about 9 or 10 lolly sticks side-by-side and measure them. I use 9 lolly sticks across (the odd number makes it a little trickier) which measures to be about 12cm high by 17cm wide.

- Print your image so it fits the measurements above.

- Glue across all the lolly sticks and leave to dry.

- Use a craft knife to cut the paper and separate the lolly sticks.

I hope you enjoy using these ideas!

*This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something using one of these links, you won’t pay any more but I will receive a small commission!

Subscribe to my weekly teaching tips email!

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

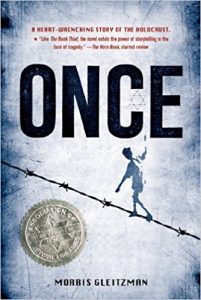

We teach Once to our newly arrived secondary students – year 7s – they are aged 11 and 12 years old. It is a fabulous novel for the secondary classroom: short, pacey, with strong characters and unexpected twists. The story is grown-up enough that my newly-minted secondary students are shocked by some of the events. It captures them with a mixture of horror and fascination. We live Felix’s adventures: this young boy speaks our language, we make mistakes and discoveries with him.

We teach Once to our newly arrived secondary students – year 7s – they are aged 11 and 12 years old. It is a fabulous novel for the secondary classroom: short, pacey, with strong characters and unexpected twists. The story is grown-up enough that my newly-minted secondary students are shocked by some of the events. It captures them with a mixture of horror and fascination. We live Felix’s adventures: this young boy speaks our language, we make mistakes and discoveries with him.